Westonia – in my verses I rehearse the truth

23. 11. 2012

In her lifetime Elizabeth Jane Weston was better known across Europe than Shakespeare. Known to her many admirers as “Westonia”, Elizabeth was born in England but spent almost all her short life in Bohemia, where she died in 1612. Her grave is still preserved in the cloister of Saint Thomas’s Church in Prague’s Lesser Quarter. In 2012 I organised a series of events to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death.

Westonia wrote in Latin, so my first step was to get together with Prague City Library to organise a competition to translate some of her poems into Czech. Here is more about the competition (in Czech), including the winning translations: https://www.unescoprague.org/ctyri-sta-let-alzbety-johanny-westonie/

The winners were announced following a ceremony at the poet’s graveside to commemorate the anniversary. The British Ambassador Sian MacLeod recited one of Westonia’s poems in Latin and the children’s choir Slavíčci (Nightingales) sang a couple of Renaissance songs. The Catholic Priest at Saint Thomas’s Father William Faix and the Anglican Chaplain in Prague Ricky Yates led an ecumenical service in the church.

A Poet in Bohemia

I also made a radio documentary about Westonia’s life and work for BBC Radio 3, A Poet in Bohemia.

About Elizabeth Jane Weston

„May the reader indulge me, and my enemy contain his bile, / Whilst in my verses I rehearse the truth.“

In her famous essay, A Room of One’s Own (1929), Virginia Woolf reflects on why women are largely absent from history books, unless they are queens, mothers or mistresses. She speculates that had William Shakespeare had an equally brilliant sister, she would have had little chance of fulfilling her potential. Woolf imagines the teenage Miss Shakespeare being beaten by her father for rejecting an arranged marriage and running away to the city, where she eventually takes her own life in the backstreets.

The life story of Elizabeth Jane Weston suggests that things could have been otherwise. She was born a few years after Shakespeare in the market town of Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, only twenty miles or so from Stratford-upon-Avon, and it seems that her social origins were just as ordinary as those of the Bard himself. Yet, scarcely out of her teens, “Westonia” was being lauded across Europe. For some years she was England’s best-known poet beyond the British Isles. She could also lay claim to being the first known Czech woman poet, since she was still a babe in arms when her family made the perilous journey to Rudolphine Bohemia and she never returned to the country of her birth.

It seems that Westonia was born in 1581; parish records suggest that her mother’s parents were well-off farmers; her father may have been an Anglican priest. All this sounds rather vague, but this is typical for the time. Elizabethan England and Rudolphine Bohemia were both places of political intrigue and danger, where favour could turn to persecution at any moment; it is no surprise that public figures would sometimes be obsessively careful about what they let on about themselves. Anything, whether truth, rumour or lie, could later be used against you. “You never lack for fraud, you have no shortage of quarrels,/ suspicion is always present, and fear always”, wrote Westonia of the Prague court. “A painted face masks what it could be harmful for many to know.”

Westonia’s poems give some clues to her biography, but these too are ambiguous. We do not even know if she was Catholic or Protestant: she is buried in Saint Thomas’s Church on Prague’s Malá Strana, a church that remained Catholic throughout the Rudolphine era, but we know that her husband was a German Protestant. A reference in one poem to “reprobate fury defiling the heavenly rites” points towards Catholicism. From her poetry it seems that her true home was in the virtual “humanist republic”, which was not sectarian. We cannot even be quite sure about her link to Chipping Norton. Westonia’s gravestone gives her precise age at death: thirty years, three months and four weeks on November 23rd 1612, but Chipping Norton baptism records indicate a birth date of 1581, although the confusion could be due to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by the Vatican in 1582.

The real mystery in Westonia’s early childhood lies in her mother’s hasty marriage, as a very young widow and mother of two small children, to the mercurial and mysterious Edward Kelley. At the time of the marriage in 1583, Kelley was in the employ of one of the most important thinkers of the Elizabethan age, the mathematician, philosopher and astronomer John Dee. Dee had faith in Kelley’s claims to be in touch with spirits, and if we are to believe Dee’s own spiritual diaries, it was on the recommendation of a spirit that the two families ended up travelling to Bohemia. Political difficulties with Elizabeth’s court and Dee’s rather mysterious friendship with a Polish Count, Olbracht Laski, also played a role.

We do not know if the two Weston children travelled with them. One of Elizabeth’s poems suggests that they initially stayed with their maternal grandparents, and travelled to Bohemia only after their death. By this time, Dee and Kelley would have been in Třeboň, under the patronage of William of Rosenberg. This, in all probability, was where Elizabeth Jane and John Francis spent a significant part of their childhood, keeping out of Kelley’s way as he concocted strange mixtures in his laboratory above the castle gate. The children are never referred to in Dee’s diaries and one theory was even put forward that Elizabeth Jane’s mother was Kelley’s second wife, and not the Joan Kelley who appears in Dee’s Třeboň diaries. But their absence from the diaries is far more likely to be a case of children being “seen but not heard.”

Kelley appears to have had great success helping Rosenberg to find ways of extracting precious metals at his mines south of Prague and this brought him both wealth and status. Within a few years the family was back in Prague moving to a very good address on what is now Charles Square. Kelley appears to have been a model stepfather. He made sure that Westonia and her brother were given excellent schooling. John and Elizabeth would have received a thorough humanist education under John Hammond, a tutor brought from Cambridge originally to teach Dee’s children. Virgil and Ovid would have figured prominently, and Latin would have been the lingua franca. Westonia later thanked her tutor: “… Muse, remember your teacher;/ he deserves to appear in your verses./ For if he had not led you to the waters of Pegasus, / you would never be read in these pages of yours.” As a girl, Westonia was unable to follow her brother to university, although their later affectionate exchange of letters when he was a student in Ingolstadt suggests that she was the more conscientious of the two. She scolds him for spending too much time strumming the lute and too little time at his books.

It was not unprecedented for girls to receive a good education. Queen Elizabeth was writing in Latin and Italian at the age of ten and her half-sister Mary Tudor was given a thorough education on the advice of the Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives. On the other hand, a decent education for girls would certainly not have been standard and it is a credit to Edward Kelley that he recognized and encouraged his step-daughter’s gifts. This was returned in her fierce loyalty to her stepfather once his star fell at the court of Rudolph, as a result of incidents and intrigues that remain obscure. Kelley’s fall from grace was spectacular. He was imprisoned twice, stripped of his newly bestowed title and deprived of the properties he had so recently gained. At some stage later, he died in prison. With the family facing destitution, Elizabeth Jane, still in her mid-teens, saved their fortune and reputation. She did so through poetry.

She wrote a string of poems to prominent figures at the Rudolphine court: various noblemen with whom the family had been in contact, even the Emperor himself. They take the form of what today we might call a “begging letter”, pointing to the unhappy plight of the family, the loss of their fortune and the sad lot of a maiden in distress. “Caesar, you are my sun; but while you hide your light,/ what will be my hope of support and salvation?” The poems clearly struck a chord with their recipients – perhaps some saw a chance of gaining some of Kelley’s lost wealth themselves – and the improvement in the family’s fortunes was spectacular. Westonia’s reputation spread fast, following the paths of rapid communication that existed between the courts of Europe.

To the modern reader, much of what we read in these begging poems seems quite distant; after a while the complaining tone begins to jar and seem formulaic. But she is writing according to conventions that would have been immediately recognized and acknowledged by her contemporaries from precedents in ancient Latin verse – notably Ovid’s exile poetry from the Black Sea. And this was a very fine art. Westonia needed to get the register just right. She was acting in a highly complex political world, and the success or otherwise of a given turn of phrase could be a matter of life or death. This is not poetry of self-expression, confession or originality in the sense that we know it in the post-Romantic world. Verse has a clear social and even political role – a status that today’s poets could only envy! It brought Westonia fame, recognition and ultimately a good marriage to the influential court lawyer, Johannes Leo. One contemporary describes them as “Leo and his Lioness”.

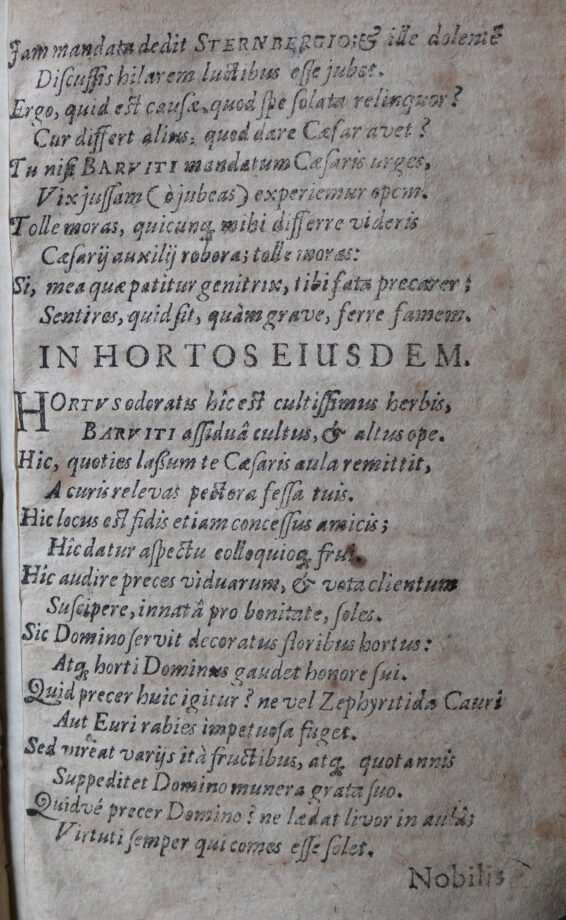

If it was the begging poems that established Westonia’s reputation at the time, it is primarily through other poems that we admire her today. Some give us a taste of Rudolphine Prague or hint, usually between the lines, at the poet’s own internal world. The most famous of all describes devastating floods, probably in 1598, and the young poet goes beyond convention in her vivid portrayal of the dramatic scenes she witnessed: “…here is a man, here a bed, and here his wife swims./ You see beams and pine trees, you see houses swimming along”. Elsewhere, in a poem dedicated to the court composer, Philippe de Monte, she writes of the power of music “In peace it restores its citizens: with unwarlike hand it keeps/ from their necks any hostile force or threat” and her poem set in the garden of the lawyer Jan Barvitius is a delightful set piece, placing the gentle harmony of the garden against the perils of the court: “What should I wish for its Lord? Not to be bruised at court/ by that Envy which is always wont to accompany virtue.”

You do not have to read far between the lines in Westonia’s poems and published correspondence to get a sense of a strong personality – perhaps the “lioness” epithet was not just a figure of speech. The poet bravely comes to the defence of the chemist Dr Oswald Croll when his works are widely damned, leaving him ostracized at the Rudolphine court. “Since Croll exposes himself so boldly to envy/ in publishing works praised by learned physicians, he has as much perfected his monuments to perennial virtue/ as he has provided a work of sincere piety.” At another point Dr Croll gives us insight into Westonia’s family life. We read a lively correspondence in which she asks him for a cure for one of her maidservants’ repeated headaches, and she also asks for a cure for sore eyes. One imagines long evenings writing poetry by candlelight.

After her marriage, Westonia’s life becomes increasingly overwhelmed by domestic obligations. She goes on to have seven children, four of whom die in infancy, but if she stops writing, she most certainly does not lose interest in poetry. She is actively involved in publishing a second edition of her verse and correspondence. In a handwritten foreword addressed to the reader in a surviving copy in the British Library, she complains about some of the details of the edition: how is it that works by other poets have been added without her permission? And why are the poems placed in such random order? This is clearly a poet who knows her own worth.

Westonia was living at a time of flux, on the very cusp of the Medieval and Modern worlds, and this accounts for many of the contradictions in her work. We will not find in Westonia a fighter for women’s rights in the modern sense. In her only poem addressed to a woman, Margaret von Baldhoven on her marriage, she states: “In all your duties remember to appease him,/ if you wish to avoid frequent strife in the marriage bed.” She very much plays the game of her male patrons, repeatedly pointing out that her poetry is just the “uncertain issue of a female brain.” She clearly does not mean it: this is a persona that enables her to function in a world where the rules are all defined by men. It is more likely to be her poetically less gifted admirers who make mistakes in metre, as she humorously reminds the lawyer, Johannes Heller in one poem: “Do me a favour, that’s all I ask, I am not attacking your poem:/ but I want to be more learned through your instruction. Hexameter verse consists of six feet; but by you/ seven have been placed there: by what reason? Teach me!” At other points she expresses views that firmly reflect the prejudices of her time. In one poem she claims that not even a converted Jew is to be trusted: “They take Prague for their Jerusalem,/ and subject and apply God to their Talmud,/ spitting on Christ and Christians.” The youthful poet is equally intolerant of romantic love in old age, stating in one of her epigrams: “When a woman who is disabled by advanced age plays,/ she foolishly feeds death with her allurements.”

It is probably no coincidence that Westonia’s most personal and moving poem was not published in any anthology during her lifetime. It is simply too personal for the tastes of the time. The poem was written on the death of her mother, who had been her constant support: “No longer will she advise me with her maternal words,/ nor will she be there for me to say, ‘Help me, mother!/ No longer will she be available to bless her descendants and me,/ making the sign of the cross on forehead and breast.”

Westonia was to outlive her mother by just six years, dying on November 23rd 1612. Her grave can still be found in the cloister of the church of Saint Thomas and includes an inscription in Latin describing her as “the delight of the Muses and an example to women.” She was writing at the tail end of a long and rich tradition of neo-Latin poetry. Her verse is limited through language and convention, contrasting with the immense breadth and wealth of Shakespeare’s vernacular. But she deserves to be read. She offers a subtle and very human perspective on Rudolphine Prague, puncturing many of the often-repeated stereotypes of “Magic Prague” that still colour our picture of Renaissance Bohemia. We have a sense a world where ideas and language itself are on the brink of huge change. Within a few years of Westonia’s death, her whole universe was to be swept away forever and Central Europe was dragged into thirty years of devastating war. Her poetry captures beautifully this fragile moment.

David Vaughan (originally written in Czech for Literární noviny, November 2012)