Sancta Familia

Triáda 2020

When I visited Colin Wels in Oxford in 2017, he showed me a little book, written and illustrated by his father and uncle as teenagers in Prague in 1938. As I read the manuscript, made up of family conversations and vividly illustrated by the 13-year-old Martin, I was drawn into their world, a world that was to disappear with World War Two and the Holocaust. I worked with the publishers Triáda to bring out a trilingual facsimile edition in Czech, German and English.

“Sancta Familia is the most faithful portrayal of middle-class life in pre-war Prague that I have ever read.”

Alena Zemančíková, PRÁVO

"The book… is exceptional in several respects. Above all it offers a far more sophisticated work of literature and art than we would expect from its 13- and 18-year-old authors. Near the beginning they write that “every sentence in this book has been spoken”, which reminds us of trends in “adult” literature at the time. The more the narrative voice points out that the text being read is not a work of art, but “only” a record of reality, the more it is reminding us that we are not reading “reality”, but words, which combine into a larger whole to create a new reality, unique, existing only in the text and brought to life at the very moment of reading."

Jiří Flaišman, KANON

Here is the text of the afterword to Sancta Familia…

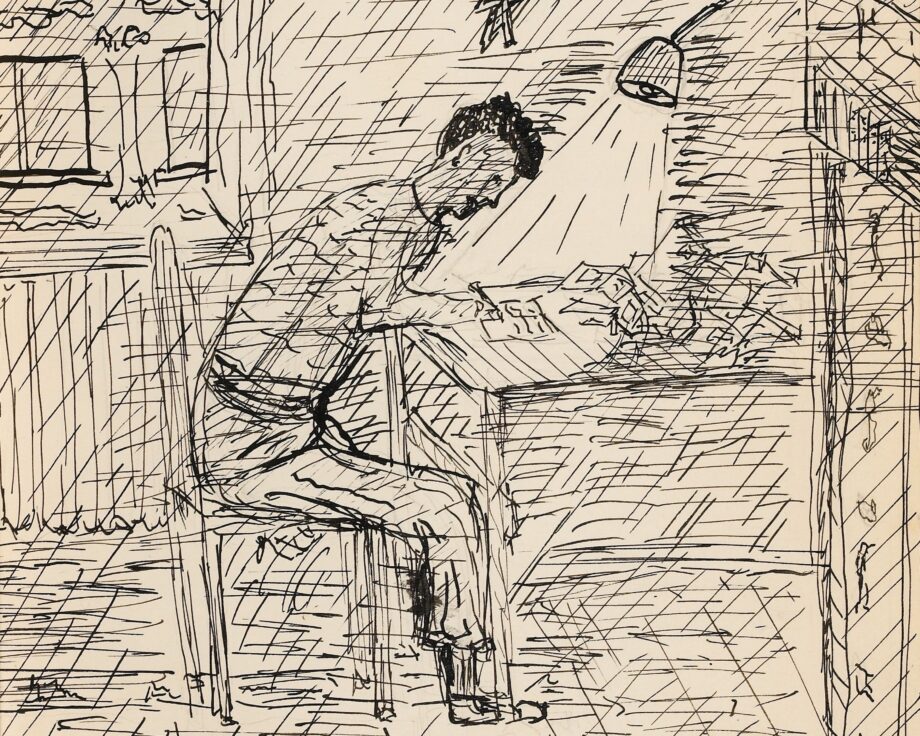

Detail of Martin’s sketch of himself writing Sancta Familia

Imagine a light and spacious modern flat with a wide terrace like the deck of a transoceanic liner. We are in Prague and it is Christmas 1938. The flat is on the top floor of an elegant new block not far from Letná Park and is home to the building’s architect Rudolf Wels and his family. They are a modern, middle-class, Prague family, living at the heart of a cosmopolitan and multilingual city.

Rudolf and Ida Wels’s sons Martin and Tomáš have decided on an unusual present for their parents. It is to be a book about the family. They hope “to capture words in flight and preserve them,” to put down on paper their conversations as they go about their daily lives. “Every word in this book has been spoken,” they write in the introduction, although “to set down every typical expression was quite impossible, because new ones are constantly appearing and old ones disappearing.” Through the book we are drawn into their lives and become an invisible family member.

The book has an intimacy and immediacy. The Wels’s are a close family and the banter between parents, children and grandmother is brimming with affection, humour and wit. The settings are everyday: shopping at the market, stopping for a snack at the “Koruna” buffet at the bottom of Wenceslas Square, squabbling over table manners, worrying about little things that seem important at the time, like Martin’s school report or how many apples to buy at the market. At one point, father and son get into an epic mock fight as Martin refuses to go to bed. This is, as Martin writes at the very end of the book, “a family as it should be.” The title, Sancta Familia, is thoroughly tongue in cheek, but it also rings true.

The illustrations are by Martin, who was an exceptionally gifted artist. He was only thirteen, but was already attending evening classes at Officina Pragensis, a small private art school. It had been set up in 1934 by the artist Hugo Steiner-Prag, best known today for his cycle of lithographs illustrating Gustav Meyrink’s quirkily atmospheric novel of Jewish Prague, The Golem. When Steiner-Prag left Czechoslovakia in 1938 to set up a similar school in Stockholm, the graphic artist and illustrator Jaroslav Šváb took over. He focused on the practical skills of the graphic artist, and this is reflected in the confidence and sophistication with which Martin incorporated his lively sketches into the text of Sancta Familia. Later, with the German occupation of the city in March 1939, the school continued to take in Jewish students, who were barred from state-run institutions.

Most of the dialogue is probably also Martin’s work. Tomáš was already eighteen, itching to leave home, and may have felt slightly self-conscious about the whole idea of the book. He is not actually present in the story. Instead the book is set in the near future, with Tomáš having just left for Paris by train, meaning that we get to know him only through his family’s conversations.

The Wels’ are a very modern family. Ida and Rudolf treat the boys as equals, sometimes Martin addresses his parents by their first names, he is always teasing them about their habits and quirks, and he jokes about his father’s vain attempts to present himself as a figure of authority. The family members know each other’s mannerisms and characteristic phrases intimately, and this makes the dialogue particularly authentic and entertaining.

It is clear that Ida and her younger son are very close. We see her trying to persuade Martin to finish his homework or to keep fit by doing more sport. Martin never ceases to wonder at his mother’s lack of interest in such important questions as what keeps the air in a car tyre or who holds the world land-speed record. In these scenes, Martin is laughing at himself too. He portrays his mother as eccentric and slightly other-worldly, but he is fully aware that he is seeing her through a child’s eyes. With his father Martin shares a love of drawing, and they conspire, usually without success, to keep out of trouble with the women of the household.

Women make up the majority. Ida’s mother, Therese Krafft, is living with the family and seems to do much of the running of the household together with the housekeeper, who is given the name Libuška in the book.

In the 1930s, Letná was a thriving and modern part of the city, on a hillside close to the Old Town and Prague Castle. It had a largely middle-class population, including many people, like the Wels family, who were Jewish by origin, but lapsed in practice. New buildings were going up all around, including the steel, concrete and glass Trade Fair Palace, the embodiment of the latest innovations in Czech “functionalist” architecture, visited by Le Corbusier in 1928.

In the streets you would have heard a mixture of Czech and German. Although by far the greater part of Prague’s population in the 1930s was Czech speaking, there was still a significant minority with German as their mother tongue. Walking down the smart shopping street Na příkopě – Im Graben in German – Martin and his mother chatter away in German. This is the heart of German-speaking Prague, and it is here that the Deutsches Haus, one of the cultural centres of Prague’s German speakers, is housed. Yet the moment they reach the end of the street, where it opens onto Wenceslas Square, they are in Czech-speaking territory. Martin jokingly tells his mother off for not switching to Czech as they cross this invisible border and go into the “Koruna” buffet.

The Wels’ are typical among educated middle-class Jewish families in being almost totally bilingual. Ida is originally from Cheb – Eger in German – in West Bohemia, a town where nearly everybody had German as their mother tongue, and she and her mother speak German, with elements of local dialect. This is also the language they use with Martin in Sancta Familia. Rudolf’s mother tongue is Czech, as he grew up in the Czech-speaking region of Rokycany, some forty miles south-west of Prague. He always speaks Czech with his sons, but they all have no difficulty switching between languages. The text of Sancta Familia skips unselfconsciously and sometimes playfully between Czech and German. Martin is attending the French Lycée, so he also speaks good French. French and English also find their way into the text.

In some respects the Wels’ are anything but an ordinary family. By the time his sons write Sancta Familia, Rudolf is already a highly successful architect. He studied before World War I in Vienna, and one of his mentors as a student was Adolf Loos, whose famous essay Ornament and Crime, had advocated simplicity and clarity, sweeping away fin-de-siècle fussiness. For a while Rudolf was working in Loos’s office, and in a letter preserved in the family archives Loos expresses his full confidence in the young Czech architect. After World War I Rudolf went on to realise many significant architectural projects in Western Bohemia, including the Miners’ House in Falkenau (in Czech Falknov, now Sokolov), several workers’ housing projects inspired by the garden cities he had seen in Britain during a visit as a student, a number of schools – including both the Czech and German grammar schools in Falkenau, and several large projects in the spa town of Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad). The Regional Health Insurance Building in Carlsbad has a distinctly Chicago feel and seems modern and original even 90 years after it was built.

In 1933 the family moved to Prague. It is not clear whether this was purely for career reasons or whether a factor was growing anti-Semitism in the predominantly German-speaking borderlands after Hitler came to power over the border.

Rudolf teamed up with the Prague architect Guido Lagus, who was also Jewish and also moved between the Czech and German speaking worlds. Together they worked on several architectural projects, mostly modern apartment blocks like the building in which the Wels’s were living at the time when Sancta Familia was written. They collaborated as set-designers on a number of Czech films, including Hej rup! one of the best loved Czech comedies of all time, directed by Martin (or “Mac”, pronounced Mats) Frič and starring the legendary Jiří Voskovec and Jan Werich. It is probably no coincidence that Martin Wels’ nickname in the family is also Mac and that it is under this name that he signs the manuscript of Sancta Familia. He clearly loves film. There are several overtly filmic moments in the book, where Martin uses a visual image to reinforce the scene. The visit to the Koruna buffet is an example: “Then all you see is a row of fine teeth, which carefully and cleanly bite off a piece of the fatty meatball”.

Guido Lagus has an amusing cameo role in Sancta Familia, in a scene at the office he shares with Rudolf. He shares his latest theory on the European crisis: “An amazing thing came to my mind during the night. Sit down! Just look, (he goes to the map), if these countries were all to join forces and if Russia were to arm herself properly, then Germany couldn’t move a muscle. What do you think?” Rudolf’s reply is a laconic, “Yes, that would be nice.” While Rudolf’s politics inclined towards the liberal left, embodied by Czechoslovakia’s founding president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Lagus had great faith in the communist avantgarde and the Soviet Union. Lagus was also active in helping the left-wing German exile community in Prague. Between 1933 and 1935 he financed and edited the magazine Neue Deutsche Blätter. Major German literary figures like Wieland Herzfelde and Anna Seghers were on the editorial team.

The scene with Lagus in Sancta Familia is one of many points in the text where humour conceals a darker reality just below the surface. Sancta Familia was written just two-and-a-half months after the Munich Agreement gave Germany nearly a quarter of Czechoslovakia’s territory. It is not mentioned in the text, but this is the reason why Ida’s mother Therese is living with the family. Her hometown of Cheb was in the annexed territory of the Sudetenland.

At the time Sancta Familia was written, it was only too clear that Hitler had ambitions to occupy the rest of the country and what this would mean for anyone on the wrong side of Nazi Germany’s racist Nuremberg Laws. The democratic institutions of the rump Czechoslovakia were already beginning to crumble, and anti-Semitism was on the rise as many Czechs retreated into more crude forms of Czech nationalism. In October 1938 the Wels family applied for a visa to the United States, and Sancta Familia has many references to their dreams of starting a new life in America. This is also a reason why Ida is encouraging Martin to work hard on his English.

Sancta Familia is set in the near future, in the spring of 1939. The family have just said goodbye to Tomáš at the railway station. He is travelling to Paris on his way to America. The rest of the family is hoping to follow soon. “You’ve no idea how glad I’ll be once we’ve all joined him,” Rudolf says, followed by a sigh, and Ida reminds him that they need to sell the furniture as soon as possible. In several of the dialogues they talk about their new life. Ida and Martin joke about setting up a fast-food stand in America – and inviting the Roosevelts to eat there.

Their hopes and dreams were not to come true. On 15th March 1939, German troops marched into Prague. A week later, the family received a letter from the American Embassy, rejecting their visa application. They were trapped in the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. A few weeks later, Tomáš did succeed in smuggling himself across the Czech-Polish border, eventually reaching Britain. In 1942 he described his escape in vivid detail in the students’ magazine of the University of Swansea where he studied engineering. He went on to serve in the Royal Air Force Coastal Command and survived the war.

Ida, Rudolf, Martin and grandmother Therese remained in Prague. Initially they managed to keep in touch with Tomáš by letter. Some of the letters include sketches by Martin in the margins. Later they were forced to move into one room of a ground-floor flat in Mánesova Street, which they shared with other Jewish families.

Towards the end of 1941 the family received a summons to join transport “V”, leaving for the Terezín ghetto on 30th January 1942. Twenty months later, on 6th September 1943, they were sent on to Auschwitz-Birkenau, to the euphemistically named “family camp”. They were murdered on the night from 8th to 9th March 1944, as the Nazis began the liquidation of the entire family camp. Therese was spared the horrors of the camps. She died in February 1941, when the family was still in Prague.

During the war, Tomáš married an Englishwoman, Joy, and later they had three children. Tomáš never spoke to his children about the past. It is not hard to see why. The sanctity of a happy family, the family we get to know in this book, had been violated in a way that was cruel beyond imagining.

It was up to Tomáš’s children, his son Colin in particular, to try to piece together the fragments of the family’s past. During the occupation, Rudolf and Ida had become close friends with the family of the protestant pastor Josef Štifter, who would often invite them to their flat above the prayer room in Římská Street, in the Prague district of Vinohrady. When they were sent to Terezín, Ida, Rudolf and Martin left their most treasured possessions in a box with the family. In February 1945, the building received a direct hit in an allied air-raid – ironically, given that Tomáš was serving in the RAF – but the contents of the box survived. They included hundreds of family letters, many sketches, photographs and documents. They also contained two remarkable hand-made books.

The first was U Bernatů, the memoirs of Rudolf’s father Šimon Wels, who had been a small shopkeeper in the village of Osek in Western Bohemia. The other was Sancta Familia, the book now in your hands.

Šimon completed U Bernatů in 1919, three years before he died. Since being published in Prague, first in samizdat in the late 1980s and several times since the fall of communism, it has become a classic, telling the story of his life and family, going back to the beginning of the 19th century. The book is instilled with the liberal humanism that we find in Šimon’s hero and contemporary, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. He lived just long enough to see Masaryk become Czechoslovakia’s first president. Šimon was a brilliant storyteller, and the book is filled with insights into rural life, especially Jewish life, in 19th century Bohemia. Originally he wrote it on loose sheets of paper, but it was transcribed by Rudolf in the first months of the occupation in his immaculate architect’s copperplate. In a short afterword, dated 1st November 1939, Rudolf writes that the work helped to keep him busy, now that the Protectorate’s racial laws banned him from working as an architect: “Often I would forget about the time – and the times – for hours on end.“

The transcript is carefully bound and on the cover is a sketch by Martin of the village green in Osek. Among many other things, U Bernatů gives us a wonderfully vivid picture of Rudolf’s childhood and we recognise the roots of many of his ideas and ideals.

In the opening chapter Šimon expresses the hope that in the future “one member of each subsequent generation will continue to write down his experiences, his pain and his joy.” In writing Sancta Familia his two grandsons were doing just this.

Between them, these two books bring to life several generations of a remarkable Czech Jewish family. And for Tomáš’s children and grandchildren, all born far from the land of their ancestors and without speaking Czech or German, it is much more than that. It is a key to a part of their identity that had been all but lost.

In 1945 Tomáš returned briefly to Prague. It soon became clear that no one in his family had survived. He visited the Štifters and returned to England, taking as many of the family things with him as he could carry. The Štifters sent on the rest later. For the next forty years he kept everything shut away in a box at the back of a cupboard in his house in England. It was only after he had suffered a stroke in 1984, leaving him unable to speak, that his son Colin decided to look inside. By coincidence Colin had a friend, Gerry Turner, who spoke Czech, and he translated the book into English. For the first time Colin and other members of his family could read about their Czech ancestors. Gerry’s Czech wife Alice brought a copy of the manuscript to Prague and the poet Zbyněk Hejda published U Bernatů in samizdat in 1987. Since the fall of communism it has been republished twice and is available in a 2011 edition, published by Triáda.

This is the first edition of Sancta Familia to be published. The manuscript has remained virtually unknown, sitting among the letters and papers, photographs and documents in the Wels family archive. It is a wonderful object in itself, which is why we felt it was important to publish a facsimile edition, preserving as much as possible of the feel of the original. Thanks to the imagination, talent and spirit of Martin and Tomáš, we are drawn into a world which is vivid and familiar, far from the grainy black-and-white anonymous images that are so often associated with the Holocaust. The stories of many thousands of other families murdered in the camps were not saved. Martin and Tomáš speak also for them.

David Vaughan, 2020