A Foreign Country

2005, Thames and Hudson

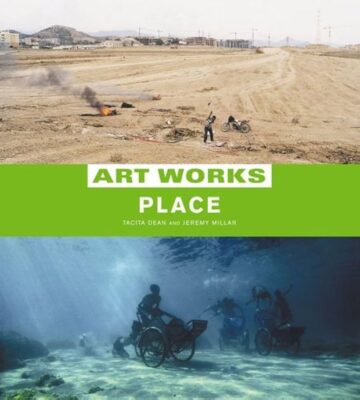

An essay on the legacy of the Lidice massacre of 1942, in Place (eds. Tacita Dean and Jeremy Millar, Thames and Hudson, London 2005)

A Foreign Country

Win Horák with Hannah Vaughan, December 2016

I have never been very interested in sport, but in the early 1990s I started going to ice hockey games with a couple of friends from the radio. We used to travel to the steel town of Kladno, famous for its hockey team. The stadium, down by the railway line, with its smoky fug, beer and sausages, was irresistible, and the fans, many of whom had come straight from their shift at the steelworks, made for an atmosphere very different from nearby Prague. Occasionally I would even report on the games for the radio and interview players in the smoke of the bar after the game.

It was as a result of these trips that I gradually learned of the tragic story of Lidice. Kladno is about fifteen miles west of Prague and on the bus I would pass the rusting corrugated iron fence and the half built twisted metal ruins of the vast memorial and conference centre that the communists had begun to build in the 1980s. With the fall of the regime, work on the project had stopped.

Lidice was razed to the ground by the Nazis on the 10th June 1942 in retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the architect of the Shoah and the man Hitler had appointed to bully the Czechs into obedience as Acting Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. The men of the village – 173 human souls – were shot against the wall of the Horák family farmhouse. Many of them had worked in the steel works in Kladno or in the local coalmines. The women and the children were sent to concentration camps. Later 82 of the children were murdered. The women who survived returned to find a field of rye where the village had stood, with a path beaten to the mass grave, where crops grew greener and faster.

A few years ago in a Prague second-hand bookshop, I found a book that the Czechoslovak Interior Ministry had produced in 1945, just months after the end of the war, a document outlining details of the Lidice massacre. I showed the book to an 80-year-old Canadian professor, David Kirk, who was visiting Prague. He was an expert on adoption and was interested in the fate of the Lidice children. He noticed a passing reference to a film that had been made in Britain during the war by Humphrey Jennings, an attempt to recreate the Lidice tragedy in the context of a Welsh village.

This captured my imagination. I arranged to see the film, The Silent Village, in London and was amazed by what I saw. It was not a historical curiosity, but an extraordinary work of art, a drama without actors, a passion play in which a village takes onto its own shoulders the fate of another village a thousand miles away. Jennings’ film was an over-ambitious and strangely contorted project that worked through his extraordinary poetic language. “I would like to be filming trees,” he told Vitkor Fischl, the Czech poet who had given him the idea for the film. “Instead, here I am making a propaganda film.”

The Nazis made their own film of the destruction of Lidice. Threatening him with execution, they used one of the best Czech documentary cameramen of his generation, Čeněk Zahradníček. They re-routed the stream and levelled the uneven parts of the ground. Their efficiency is carefully recorded. The images of Lidice burning have become familiar to every Czech.

In 1999 I made a documentary about The Silent Village for Czech Radio, visiting Jennings’ chosen village of Cwmgiedd at the head of the Swansea Valley. I travelled through Wales with the countryside around Kladno in my mind. I looked for similarities, and, of course, I found as many or as few as the mood of the moment.

In the Art Nouveau café of the Obecní dům in Prague, I met Viktor Fischl. He was nearly 90, living in Jerusalem, one of the grand old men of Czech letters.

The voice of the seedlings under the furrow,

of the young shoots driving up into the spring,

of the green buds born from the trunk’s mutilations.

He told me of the long poem The Dead Village which he had written hours after he heard of the Lidice massacre from his wartime exile in London. The poem gave him the idea for the The Silent Village, as a way for the people of Britain to identify with the fate of occupied Europe. This was what Humphrey Jennings then tried to achieve. Viktor Fischl believes he succeeded, that the villagers of Cwmgiedd “lived Lidice.” Today we cannot know. All we have is the film.

In Cwmgiedd, The Silent Village has become part of the history of the village. A whole generation of villagers appeared in the film. A moment in the village’s life is captured. People see themselves when young, or their parents and grandparents, growing a little more distant each time they see the film.

I watched the film with Mair Thomas in the living room behind the family butcher’s shop in Cwmgiedd. “It sends a shiver down my spine to see them. All dead.“ She is talking of the villagers of Cwmgiedd, her relatives from 60 years ago. Perhaps she is also talking of the people whose fate they are enacting. If I were to ask, she would probably not be sure. Most of the actors of Cwmgiedd have now joined the men and children of Lidice. As the film runs in the background Mair recites passages from memory.

„I have just had a letter to inform me that there is no more Welsh to be spoken in this school…

…But, children, I want you to promise me one thing. Do not forget your Welsh. Speak Welsh at home, on the roadside, at your play, everywhere. Will you promise me not to forget your Welsh language?“

„Yes, Miss Daniels.“

Ewart Alexander was a little boy at the Cynlais School. We see him being taken away with the other children to a waiting Gestapo truck. He grew up to be a writer and has written two plays about The Silent Village. In the second, which he wrote shortly after my first visit to Cwmgiedd three years ago, a villager from Cwmgiedd meets a survivor from Lidice, in a meeting characterized by tension and then reconciliation. I have visited Ewart several times. With nostalgia he recalls memories from the filming, but each time he recounts the memories they satisfy him less. The thought of the other people, the victims of the real atrocity in that other place, will not go away. It adds unease to nostalgia for a summer of filming all those years ago.

A booklet was produced in 1943 to accompany the premiere of The Silent Village. In his introduction, the then Czechoslovak foreign minister in exile, Jan Masaryk, wrote that two men of Lidice were not murdered. They were airmen in the RAF and one of them had married a Welsh girl.

In fact she was English. Perhaps her name – Win – sounded Welsh to Masaryk, perhaps it was just licence. Her husband was Josef Horák from Lidice, a pilot in the Czechoslovak 311 Squadron.

When Pavel Štingl and I were working on our film, The Second Life of Lidice, we had little difficulty finding Win. Before I even knew of The Silent Village I had interviewed her sister-in-law, Anna Nešporová, in Lidice. Anna Nešporová was one of the women who had survived. Apart from her brother in England, all her family had been shot, and it was against the barn of her family’s farm that the 173 men were murdered. In May 1945 Anna walked 300 kilometres home from Ravensbrück. She is small and extraordinarily strong. Anna always stands as she talks of the events of the war – sometimes up to four hours as she remembers details.

Win is tall and dignified. She is what Czechs would call a “dáma”. The English word “lady” would be a woefully inadequate translation. Win has never lost the beauty of her youth, and it is easy to imagine her with her handsome young Czech pilot husband. She lives in Stratton-St-Margaret, on the outskirts of Swindon.

In the weeks after the war, Josef, Win and their two sons moved to Czechoslovakia. The boys had never seen Lidice and at first played in the field of rye. They were the only intact Lidice family. Lidice women were slowly trickling back from Ravensbruck, and gradually 17 surviving children were found.

Within three years Win and her family – the last people of Lidice to bear the name Horák – were driven out of Czechoslovakia. It was a grotesque twist of fate, shared by many other Czechs and Slovaks who had fought in the West. Lidice was brought under the new Stalinist order.

The family returned to Britain. With British passports, Win and the children were able to leave legally. Josef had to smuggle himself across the border. He rejoined the RAF, but tragically he died a year later when his plane crashed, and Win brought up Josef (junior) and Vašek in her native Swindon. She was forced to break all contact with her sister-in-law Anna. Having lost nearly all her family in 1942, Anna had now lost her surviving brother. She tried to send a handful of Lidice earth to her brother’s funeral, but it never got beyond Ruzyně Airport.

Win’s surviving son – called Josef after his father – does not speak Czech. He has no memories of his brief childhood in a suburb of Kladno, a few hundred yards from old Lidice. He feels half his life amputated. Josef’s only memory… he thinks… he is not sure… is a smell, a pig-killing, not an unpleasant smell. Perhaps it was a celebration after years of rationing. A fragment of Czechoslovak newsreel shows the family at Christmas 1946. „Happy Christmas to the whole wide world“, says one of the boys, his English already marked by a strong Czech accent. For Josef there is no hint of familiarity.

With our film crew we travelled to Cwmgiedd, along with Pavla Nešporová from Lidice. Pavla is the granddaughter of Anna and the great-niece of Win. She grew up in the dying days of the communist regime. At home she had her grandmother’s memories; in public she was fed with a Lidice that was to be found on a podium on the 10th June every year, bedecked with hammer and sickle and the ill-fitting grey or brown suits of regime officials.

When she visited Cwmgiedd there was no moment of recognition or identification, but there was something else. With Pavla we filmed the Cynlais Primary School harvest festival in the Yorath Chapel, Cwmgiedd, in October 2001, a month after 9/11. The children laughed as the chapel filled with a white cloud from our cameraman’s artificial smoke machine in the minutes before the service started.

The children sang and the parents looked down from the gallery, and for a moment Pavla did see a mirror to her own village. “I imagined how it would have been in the old Lidice“.