Ivan Blatný – The Poetic World of Newt

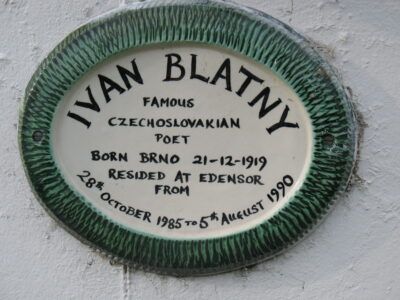

Ivan Blatný was one of the great Czech poets of the 20th century. In the words of the novelist Josef Škvorecký, “he created poetry of absolute originality and great beauty, devoid of cliché, neither patriotic nor political.” Yet Blatný spent the greater part of his life in psychiatric institutions. Much of his most celebrated poetry was written in Saint Clement’s Hospital in Ipswich, where he was “rediscovered” after years of quietly throwing his poetry away at the end of each day. I travelled to Brno, Prague, Ipswich and Clacton-on-Sea in the footsteps of this brilliant and elusive poet.

“I liked it, I listened, I remembered”

Josef Škvorecký

“Radio 3 told his story in loving and surprising detail. The Poetic World of Newt, presented by David Vaughan, had all the virtues of traditional Third Programme documentaries.”

Joan Bakewell (Pick of the Week, BBC Radio 4).

“It’s powerful, true and compassionately told by David Vaughan.”

Gillian Reynolds, Daily Telegraph

“It's beautifully done, a reproach to our ignorance of a great modern writer."

Martin Hoyle, Financial Times

The Poetic World of Newt

In 2007 I made The Poetic World of Newt, a documentary about Ivan Blatný’s life and work for BBC Radio 3.

About Ivan Blatný

When Václav Havel made his first visit to Britain as Czechoslovak President just months after the fall of communism, he made a point of meeting and thanking the nurse, Frances Meacham, who for years had salvaged Blatný’s verse – written on scraps of paper and in children’s exercise books.

In the 1940s the youthful Blatný had been one of Czechoslovakia’s great literary hopes. His rise to fame had begun during the wartime German occupation with two successful collections, evoking the atmosphere of his home city of Brno in a mood of nostalgia and melancholy. In his early twenties he shifted towards a very different style, breaking down conventional poetic forms and seeking inspiration in the everyday. He flirted with communism, and after the Soviet liberation of Czechoslovakia came to be seen very much as a poet of the new establishment. His sudden dramatic defection to London in March 1948 – the first defection of a writer or artist following the communist putsch in Prague a few weeks earlier – came as a complete shock.

Exile from the fledgling Stalinist regime brought him isolation, and during his first months in Britain he showed growing signs of mental illness. Blatný was admitted to Friern Barnet Hospital in North London. From then until his death in Clacton-on-Sea in 1990, he spent little time out of institutions.

As recently rediscovered secret police files reveal, the regime neither forgave nor forgot. Czechoslovak foreign intelligence tried to “re-acquire” Blatný “for active propagandistic use” in the late 1950s – giving him the bizarre codename “Newt”. Their attempt failed abysmally. Agent “Kolařík” gave up, concluding at the end of his final report that “Newt is, in fact, insane”.

Ivan Blatný was not insane. His mental illness made it difficult for him to cope with daily life. He could be infuriating and obsessive, his moods oscillated between euphoria and what he described as “blue”, but his mind remained as sharp as his sense of humour.

Blatný’s poetry from the hospital years is immensely original, often humorous and at times bizarre. In my documentary the scholar of Czech literature Robert Pynsent sums it up nicely: “He combines the two earlier periods of his writing and allows them to flow over him, within a cultural context that is in his memory and a cultural context of him in mental hospital, and lets those two contexts flow together in a new sort of verse.” The poems jump between languages; references to Brno before the war are juxtaposed with fragments of British media culture that he picked up during hours in front of the television in the hospital. They bridge time and cultures, but they are far from being the wanderings of a disturbed mind. With tongue in cheek the Blatný scholar and translator, Martin Tharp describes the later Blatný as the first “TV poet”.

There is an excellent biographical novel about Ivan Blatný in Czech by Martin Reiner (Básník /Poet/, 2014, Torst)

Forgotten audio recordings of Ivan Blatný

In 1982 the Norwegian/Slovak film maker Lubo Mauer made a documentary about Ivan Blatný for Norwegian television. A year earlier, he visited Blatný in Saint Clement’s Hospital, Ipswich, to prepare for the filming. He spent several hours with the poet and recorded their conversations. I contacted Lubo Mauer when I was researching into Blatný’s life and he sent me the cassettes on which he had recorded the interviews. The sound quality is sometimes poor and their conversation goes back and forward between English and Czech, but these informal interviews give us some fascinating insights into Blatný’s life in the hospital. They also remind us that, although Blatný had been living for years as a patient in a psychiatric hospital, his mind was still as sharp as it had ever been.

Transcriptions of the material were published in the literary magazine Souvislosti (Year 24, 2013, Volume 2, pages 52–77).