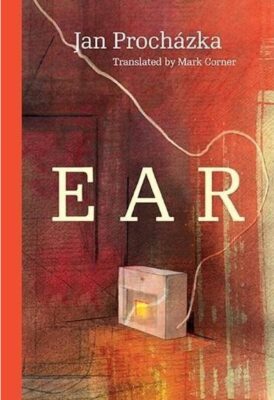

Ear

Karolinum Press 2022

I was recently invited to write an afterword to the first English translation of one of the classics of Czech writing from the late 1960s. It is a brilliant book and its author, Jan Procházka, is a much neglected Czech writer.

Afterword

It was during his military service that Jan Procházka first came across the work of Ernest Hemingway and was inspired to start writing. Hemingway remained a strong influence throughout his career. According to his daughter, the writer Lenka Procházková, he always kept a photograph of Hemingway on his bookshelf, and for years the family assumed it was a relative. In 1961, the year Hemingway died, Procházka visited Cuba and saw the simple white farmhouse where he had lived. His daughter remembers that one of his dreams was to find a similar place to live and write.

Jan Procházka was one of the most popular Czech authors of the 1960s and is still read widely, but he is best known for his collaboration as a screenwriter with the filmmaker Karel Kachyňa. Most of his prose writings have a parallel life in film, and Ear is no exception. Its 1990 edition, the first to appear in Czechoslovakia, two decades after it was banned, bears the subtitle “film story”, and this has been kept in all subsequent editions. The book can be read as a screenplay, but this does not in any way detract from its value as a literary text. In his 1968 collection of articles and essays Politics for Everyone, Procházka wrote that, just like a play or a novella, “writing a screenplay is storytelling” and not a “set of technical directions”. In Ear simple sentences or sometimes just fragments of sentences set each scene and frame the dialogue with an economy that is overtly poetic. Like Hemingway, Procházka distils surface details without explanation or interpretation. The power of the writing often lies in what remains unsaid. Just as Hemingway honed his craft during his years as a journalist, Procházka owed his economy of style at least in part to the discipline of screenwriting.

Procházka is a master of dialogue. The dialogue in Ear is realistic, full of everyday slang (which is challenging for a translator), but at the same time it is pared down and fragmentary, hinting at a hinterland that is painful, unresolved and in the case of this story, sinister. Procházka was an exact contemporary of Harold Pinter, another master of the unsaid or half-said, but unlike Pinter he nearly always remains grounded in time and place We would be hard pressed to find a scene in Ear that could not have happened. If the story seems absurd or surreal, this stems from the grotesque realities of its setting in early 1950s Czechoslovakia. Procházka is at home in the tradition of realism, but, as with Hemingway, it is a concentrated realism that goes beyond the moment. “The writer should not write things which instantly, in the moment they are written, are wiped out like chalk words on a blackboard,” he wrote in an undated text which his daughter Lenka found in his drawer after his death.

Ear has also been compared to Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee was another contemporary, and Lenka Procházková recalls that her father was hugely impressed when they went to see Mike Nichol’s 1966 film adaptation with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Like Albee’s play, Ear opens with a drunken middle-aged couple arriving home after a party and the story takes place in the space of one night. The liquor-fuelled sparring between the two protagonists is central to both texts, as is their sense of being trapped in their roles, and in both there is an uneasy relationship between illusion, self-delusion and reality. They also share many moments of dark humour. But Ear has a political side that is specific to Procházka and the extraordinary times he was living through. Although the hell in which they are trapped is partly of their own making, the catalyst for the crisis faced by Anna and Ludvík comes directly from the political reality of the world they are living in. Procházka sets the story in the Stalinist Czechoslovakia of the early 1950s, the time of political purges and show-trials, when a night-time knock on the door could have catastrophic, even fatal, consequences. By the time he was writing Ear, towards the end of 1968, this was already history, but the atmosphere of fear had returned. In August 1968, the Soviet Union had led the Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia, bringing an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. In banning the book and the film, the censors unwittingly confirmed the relevance of the story to their own time.

It is one of the paradoxes of the period after 1968 that many of those who were most ruthlessly persecuted had previously been active communists themselves. Jan Procházka was no exception. During the thaw of the 1960s, he had been one of the country’s most visible and overtly political writers, an articulate advocate of reform communism. He had charisma and people who heard him speak in public recall that he radiated energy and authority, “like a bulldozer, with a gift for persuading people that he was right,” in the words of the playwright Pavel Kohout. When the Party Secretary Alexander Dubček introduced the radical reforms of the Prague Spring in 1968, many in the younger generation saw Procházka as a future Czechoslovak President, a symbol of “socialism with a human face”. All this was to end with the invasion.

Procházka was an early convert to socialism. He was born on 4th February 1929 in Ivančice in South Moravia, the south-eastern corner of today’s Czech Republic. It is a small town at the heart of a traditionally Catholic agricultural region known for its vineyards and gentle climate, and Procházka’s writing often returns to this rural world. At sixteen he witnessed the Red Army’s liberation of his hometown from the roof of his family’s farmhouse, and like so many of his generation, he joined the Communist Party as soon as he was old enough, “convinced that socialism would mean a new, more just order.” This led to tensions with his father, who as a proudly independent farmer at first resisted joining the local farming collective after the communists came to power in 1948. Procházka left home to study at the Agricultural College in Olomouc, about a hundred kilometres north-east of Ivančice. Soon afterwards he was appointed head of the State Youth Farm in nearby Ondrášov.

His first collection of short stories A Year in the Life (1956) is a celebration of collectivisation, based on his experiences on the farm. The book was not a success, and he was quick to recognise its flaws. The stories were formulaic and artificial, driven by his political enthusiasm rather than his powers of observation. His novella Green Horizons, written three years later, was very different. It has a similar setting but his portrayal of life in the countryside of the Czech borderlands, resettled after the violent expulsion of the country’s German minority, is anything but idyllic. The characters are drawn with a subtlety that challenges the crude templates of socialist realism prevalent at the time, and he writes with the authority of someone familiar with the land. It is lyrical but shuns nostalgia or pathos.

Thanks to the success of Green Horizons, Procházka was noticed by the writer František Kožík, who saw a filmic quality to his writing, with its strong characterisation and eye for telling detail. On Kožík’s recommendation, he was hired in 1960 as a script editor and then screenwriter at the Barrandov film studios in Prague. Soon afterwards he began to work with Karel Kachyňa, who was five years his senior and already a successful filmmaker. Over the next decade they were to make a dozen films together. Many of these started as short stories or novellas, although Procházka’s literary imagination is so closely entwined with film that the roots of film and book are often hard to separate. He became a master of what he called the “literary screenplay”. Christopher Isherwood’s famous words, “I am a camera with its shutter open,” can be applied almost literally to Procházka’s writing, but when Isherwood’s narrator in Goodbye to Berlin adds that he is “quite passive, recording, not thinking,” this could hardly be further from Procházka’s approach to writing and screenwriting. Procházka is anything but passive, carefully composing every image and every movement, with a clear idea of what he wants to say.

In a rather old-fashioned sense he is a moralist, and this can be seen in all his work during the 1960s. “Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. To espouse the idea of right and wrong is neither stupid, nor is it conformist or conservative,” he writes in Politics for Everyone. When he talks about his faith in socialism, his interpretation of the word is so broad that it could be replaced with “democracy” or “humanism” without a significant shift in meaning. His moral and political compass is steered by the idea that it is important to watch closely and to see things as they are, to acknowledge society’s flaws and where necessary to draw attention to them, but without passing judgment. Politics for Everyone begins with the words: “Since time immemorial, the only way we have managed to find truth is by forcing ourselves to overcome our natural inclination to lie.”

This moral impulse brings with it an acknowledgement of human frailty. Procházka’s protagonists are always flawed, and this is what defines their humanity and makes them attractive. In the story Magdaléna from 1963, the heroes are an alcoholic and a prostitute, played brilliantly by Rudolf Hrušinský and Hana Hegerová in Kachyňa’s film from the same year. Neither the story nor the film impressed the political establishment – these were hardly role models for a socialist society – but Procházka’s defence was simple: this is a story of human hope (Hope is also the title of Kachyňa’s film), and this is what the two protagonists find in one another. In Ear, we are given a similarly nuanced portrait of an imperfect relationship. Anna and Ludvík’s marriage is deeply dysfunctional, and their endless sparring occasionally spills over into violence, but for all this rawness, inseparable from the agonisingly claustrophobic situation in which they find themselves, the writer portrays them with sympathy. He pokes fun at his protagonists, but there are moments of tenderness and unexpected poetry.

Often it is the female characters who are developed most strongly in Procházka’s work. The short story Magdaléna was the fourth in a series of portraits of women, each of which he adapted as a screenplay. Starting with the twelve-year-old Jitka and her unlikely friendship with a hospital patient who is struggling to walk and ending with the eponymous prostitute, each story reminds us in its own way of the gulf between the loudly trumpeted claim that women have achieved equality in socialist society and the reality of their lives. In Politics for Everyone, he mocks the poet who claims that “women are flowers and mothers.”

Procházka himself was for many years the only man in a household of women, made up of his wife Mahulena, their three daughters, Lenka, Iva and Krista and Mahulena’s mother Marie, whose husband had been killed by the Germans during the war. He was devoted to his family and went out of his way to encourage his daughters to think independently. Many of his stories and screenplays have children – girls or boys – as their central figure, rebellious, getting into trouble, but usually with more wisdom than all the adults put together. His daughter Lenka remembers how he would tell her a bedtime story and then hurry to his study to write it up on his typewriter. Lenka and Iva both went on to become successful writers.

Procházka had a gift for putting a deeply human story into the context of broad historical events and in so doing, casting doubt on the prevailing narrative of those events. This is the case with the three best-known films he made with Karel Kachyňa, Ear (1970), Long Live the Republic (1965) and Coach to Vienna (1966). While Ear blurs the line between victim and perpetrator at the time of the 1950s purges, the other two films offer an ambivalent view of the liberation of Czechoslovakia at the end of the Second World War. The strongly autobiographical Long Live the Republic, set in the rural world of South Moravia at the very end of the war, is not a celebration of victory. The cruelty of war seeps into the peace and is presented in stark contrast with the innocence of a twelve-year-old child, Olin. In Coach to Vienna, a young woman, who has seen her husband hanged by the Germans, recognises the humanity of a young German soldier and is unable to kill him in revenge. Criticised for portraying perpetrators as victims, Procházka replied that “most victims of war are innocent. How could it be otherwise? Has it ever been the case that those who are sent to fight have wanted to go to war?”

At the height of his success at the Barrandov studios, Procházka established an unlikely personal friendship – or near-friendship – with the then Czechoslovak President Antonín Novotný. According to Lenka Procházková, it started with a mistake. Novotný had heard a radio report by someone with the same surname talking about agricultural reforms and expressed a desire to meet this young comrade. The wrong Procházka was summoned, but he made such an impression that they began to meet regularly and he became the president’s advisor for film. He sat on various official bodies, including the Communist Party’s “ideological committee” where he was able to use his influence to help fellow filmmakers, including Jan Němec and Věra Chytilová, to get past the censors. He must have had plenty of glimpses into the murky corridors of power, and these experiences would have helped him when writing the grotesquely realistic scenes at the boozy government reception in Ear.

Procházka knew he was treading a fine line. His outspokenness was already being noticed by hardliners and the secret police. At the Congress of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in June 1967 he was one of several writers who openly criticised the political status quo. His status as “Candidate for the Central Committee of the Communist Party” was suspended, and there could have been more serious consequences, had it not been for the reforms of the Prague Spring that began a few months later. Procházka became a voice for change. At a public discussion in March 1968, he gave a now legendary speech, in which he argued that elections in communist Czechoslovakia were nothing more than a façade, “an operetta, in which the pet dog Dingo might just as well vote on behalf of the whole family.” It is hardly surprising that he became a hero of the younger generation, saying out loud what they felt but did not yet have the confidence to articulate. Before long he was arguing for an end to one-party rule.

A week before the Soviet-led invasion on the night from 20th to 21st August 1968 he wrote a text arguing why it could never happen – that the Soviet Union would lose face and that its Warsaw Pact allies would never be willing to join in. Lenka Procházková recalls that one of the first things he did on hearing that tanks had crossed the border was to tear up the text he was in the middle of writing and try – unsuccessfully – to flush it down the toilet, a scene that has immediate echoes in Ear. For Procházka, as for the great majority of his compatriots, the invasion came as a deep shock, but it did not break him. Unlike many of those who had played an active role in the Prague Spring, he decided not to leave Czechoslovakia, and unlike many of those who stayed, he refused to acknowledge the official narrative of the invasion as “fraternal assistance”. “We may have lost hope,” he observed, “but we must not let them notice it.” Over the coming months, he continued working on several screenplays, and he wrote Ear in the space of just three weeks of feverish hard work. He was under ever closer surveillance from the secret police as Czechoslovakia slid into the period known euphemistically as “normalisation”, a drip-by-drip return to hard-line rule.

On 16th January 1969 the twenty-year-old student Jan Palach doused himself with petrol and set himself alight at the top of Prague’s Wenceslas Square in protest against a creeping return to censorship and growing public acceptance of the invasion. In the days that followed Procházka commented: “I think that Jan Palach’s sacrifice might really succeed in slowing down or stopping our growing tendency towards collaboration. Above all in its worst form – apathy. Of course, it is the romantic act of a young person. I fear that an older person would rationalise everything and no longer be capable of such an act. We would use countless excuses to persuade ourselves that it made no sense.” Eight years earlier, at the end of the story Lenka, Procházka had compared the impulsive and courageous twelve-year-old heroine to Joan of Arc, and here we see him again, refusing to distance himself from the impulsive and romantic idealism of the young. Lenka Procházková remembers that there was always something of the child in her father and this inoculated him against any form of cynicism.

Remarkably, Procházka and Kachyňa were given the go-ahead to make the film Ear, and it was completed just before the end of 1969. It tells the story of one night in the life of a deputy minister and his wife, in the wake of the minister’s arrest during the purges of the early 1950s. It is a perfectly crafted domestic political drama, a suffocatingly dark Hitchcockian thriller bordering on horror, with brilliant performances by Radek Brzobohatý and Jiřina Bohdalová as Ludvík and Anna, terrified that they are the next in line. Procházka and Kachyňa knew from the start which actors they wanted in the two roles, and Procházka was able to write the screenplay with both in mind.

As a study of the impact of surveillance, intimidation, fear and uncertainty on the individual, the film takes the pulse of its time, a fact that was to seal its fate. It was shown only once to an audience of a few dozen at the Barrandov studios. Lenka Procházková remembers that when the lights went up there was complete silence. No one clapped and just a few were brave enough to shake hands with her father. Everyone knew that the film would be unacceptable to the censors and would be banned before it even reached the cinemas. The screenplay had a similar fate, although it was eventually published in 1976 in an exile edition in Cologne.

The secret police launched an unprecedented campaign against Procházka that was to set the tone for their tactics of bullying and humiliating writers and dissidents over the next twenty years. They had made secret – and illegal – recordings of private meetings between Procházka and the writer and philosopher Václav Černý, during which Procházka had openly criticised some of the politicians of the time. These conversations became the centrepiece of a television documentary, broadcast in April 1970, carefully edited to discredit Procházka to the maximum. Paradoxically, for a writer who had spent years giving a voice to people who would usually find themselves marginalised, he was portrayed as arrogant and condescending, detached from the people. The documentary was followed by damning articles in the press. Procházka wrote letter after letter to defend himself, but he had no chance against a systematic, state-sponsored campaign. One of the most prominent literary figures of the Prague Spring, Procházka’s fellow-writer Ludvík Vaculík, wrote to the Chief Prosecutor, protesting against the blatant violation of the law in broadcasting the recordings. He referred indirectly to Orwell’s 1984, but his words could just as easily be applied to Ear: “If you do not intervene to stop this, we shall soon find the nightmare utopia of the novel coming true, with people living like insects under a magnifying glass, monitored by the microphones and cameras of anonymous, untouchable and unaccountable usurpers.” His letter remained unanswered.

Shortly afterwards, Jan Procházka was diagnosed with colon cancer. Had he not been in hospital, he would have been arrested in July 1970, in one of the waves of secret police arrests of people who continued to criticise the occupation. Police records show that they suspected him of feigning the illness and tried to have him transferred to the prison hospital in Ruzyně. He was able to spend Christmas at home, but his condition was worsening and he died on 20th February 1971, aged forty-two. The secret police tried to prevent the funeral from taking place in Prague, afraid that it could become a rallying point, and when that failed, they made a point of compiling a complete list of those who were present. The darkest period of normalisation was beginning, and from that moment onwards the choice was clear: keep silent or become a pariah in the eyes of the state.

Ten years after his death, his daughter Lenka remembers moving out of the flat where the family had lived in the Prague district of Hanspaulka. She warned the new tenants that they might come across listening devices from her father’s time. “They called us back to say they’d found twelve, including the bathroom, the toilet and the balcony.” Ear had not exaggerated.

In the end Ear was to outlive its censors. There was huge excitement when the film was first shown in Prague’s Lucerna cinema in January 1990, just weeks after the Velvet Revolution. Shortly afterwards the book was published for the first time in Czechoslovakia. In the same year the film was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes. Both the book and the film were seen not just as examples of the very best of 1960s writing and cinema, but also as a metaphor for the Czech experience of the twentieth century. Unlike many parts of Europe, this country was not devastated by war. It experienced instead a particularly insidious form of totalitarian rule, first under Nazi Germany and then as a satellite of Soviet Russia. At first sight, life went on as usual. By making certain compromises people hoped to get by, although at regular intervals they would be expected to humiliate themselves by demonstrating their loyalty in public. Sometimes the rules would change – suddenly and arbitrarily – as we see at the beginning of Ear, when Anna and Ludvík find out that Ludvík’s boss has been arrested but have no idea why. Keeping people in a state of constant uncertainty is a tried and tested means of control. At the same time Ear shows how the regime was able to permeate every intimate corner of the private sphere. There is literally nowhere in the house where Anna and Ludvík can escape the “ear”. Their private sphere no longer exists, but part of their tragedy lies in that they are fully aware that they have no right to complain. They have been compromised and have become complicit in the crimes of the regime.

For readers unfamiliar with Czechoslovak history, a few details in Ear need explaining. There are references to Edvard Beneš, the last pre-communist President of Czechoslovakia who died in 1948 just months after the communist takeover. The country’s first President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk is also mentioned. Both names, closely associated with the pre-war democratic First Czechoslovak Republic, would have been taboo in 1950s Czechoslovakia and then once again after the 1968 invasion. Just by mentioning them in connection with her husband, Anna is potentially compromising Ludvík’s career in the communist hierarchy. Equally dangerous are references to Anna’s middle class roots as the daughter of a publican. The good communist is expected at least to pretend to have a working-class background. At one point Anna and Ludvík argue about the financial difficulties they were in just before the communist takeover. By embracing the “revolution” in 1948, they found a convenient way of wiping out their old debts. Like many people in the 1950s – and equally after the Soviet invasion of 1968 – they were motivated to toe the line by opportunism rather than idealism. On two occasions Ear refers to politicians who have changed their surnames. This is a reminder that in 1950s Czechoslovakia, just as in the Soviet Union, people with Jewish-sounding names were looked on with suspicion. In the anti-Semitic show trials of the early 1950s, many prominent Jewish politicians were persecuted, regardless of their loyalty to the regime. Several were executed.

By showing in vivid detail how the system works, Procházka’s book hollows it out and exposes its cruelty and cynicism, as it turns its victims into collaborators and its collaborators into victims. Ear could not have been written at any other time, but its context provides the framework for a psychological drama that is universal. The book is a deeply empathetic, but unflinchingly forensic study of the way people behave when placed under intolerable stress. We may not like Anna and Ludvík, but Procházka does not offer us the luxury of looking down on them. We know that we would probably behave in a similar way. That is the brilliance of this book. Anna and Ludvík are “only human”, but so too are the forces that torture them, and in that way the cycle is perpetuated.

David Vaughan