An Act of Transgression

8. 1. 2015

Berlin and Prague in November 1989. Address to the Prague Model United Nations (an international conference for high school students).

As you know, there were some quite dramatic things going on this part of the world 25 years ago. If a time machine could magic us back to this point exactly a quarter of a century ago, we would find an incredible buzz in the air, an atmosphere of genuine euphoria that I do not remember experiencing before or since. If we were to walk just a few hundred yards down the hill from this point to Prague Castle, we would find a brand new Czechoslovak president, speeding down the long corridors of the castle on a child’s scooter. He had been elected just a week before – twenty-five years and ten days ago. The new president on the scooter was the playwright Václav Havel – who just a few months beforehand had been a dissident. Not only that – he had actually been in prison for the crime of taking part in what the regime saw as an act of “public disorder”. Now he was head of state. There was something miraculous in what happened in those days just after the fall of communism. It was not a time for cynics and sceptics.

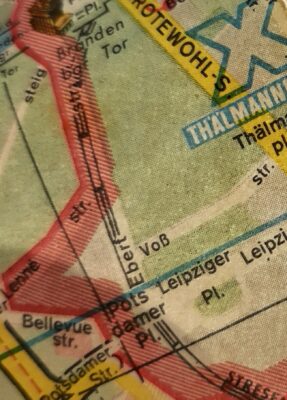

As a student I had spent a year in West Berlin from 1986 to 1987 and I remember my first impressions when I saw the Berlin Wall. I was surprised that it wasn’t particularly high, it was so closely guarded that it did not need to be. It was an incongruously banal element in the landscape. I have a second, more vivid memory of my first encounter with the Wall. It is of watching the birds – mostly sparrows – flying back and forth between the two Berlins. They were ignored by the border guards and for the birds themselves the wall was completely irrelevant – it simply wasn’t there. Given what the Wall meant for human beings – the danger of being arrested or even shot – this ordinary sight of plain brown birds flying back and forth, seemed almost surreal. It was nature offering its own little gesture of defiance, saying: “You people can do whatever you want, but we are not going to play your game.”

I was in Berlin again in November 1989. This meant that I missed the drama of the Velvet Revolution in Prague, but I was luckily enough to be in the midst of the excitement of the fall of the Berlin Wall, which was the catalyst for Czechoslovakia’s revolution a week later.

As you can imagine, that period has left me with some of the most vivid memories of my life. It has also influenced deeply the way I look at the world as a journalist.

I shall explain why. First of all I realized that the impossible can happen. Overnight everything changed. The journalist has no right to be either cynical – assuming that things will not get better – or complacent – assuming that things will not get worse. The world we live in today will not be the world of tomorrow – and to understand that sometimes requires us to use our powers of imagination and empathy to their limits.

My most enduring memory of those days in Berlin is of something much more tangible than the political changes. What I found more exciting than anything else was the physical reality of the Wall being breached, of going from one side to the other. The miracle at that moment did not lie in the collapse of the ideological house of cards that made up the East German regime, the miracle was in the fact that people who had been kept separate were no longer separate: it was a million personal encounters with the unknown – it was the beauty of people going across and meeting other people on the other side. And it was not a straightforward journey from one side – unfreedom, to the other side – freedom. Instead it was an untidy and exciting mingling – it was like paints mixing on a pallet.

Oddly enough, the word in English that comes nearest to capturing the sense of this act of going across is the word “transgression” – from the Latin transgredi – which translates literally as “to go across”. But the word “transgression” has an almost entirely negative connotation in English. It implies breaking the rules, breaking the law, or some kind of distortion or perversion. What I learned during those days in Berlin is that transgression – in the sense of going across from the familiar into the unfamiliar – can be one of the most liberating things of all – and it brings us very close to the core of what freedom is. Freedom by its very nature is uncomfortable, messy and challenging. Similarly, in the imposition of order, we often find the very opposite of freedom. A recent biography of Václav Havel by Michael Žantovský reminds us that Havel spent much of his life trying to defend civil society against “the restoration of order”. There is no paradox in this. I would argue that it was that little bit of the anarchist and the childish rebel in President Havel that made him such a great democrat.

Democracy needs people who break the rules and break taboos. That is also why we need to cry out so loudly against acts like yesterday’s murder in Paris of several satirical cartoonists from the magazine Charlie Hebdo. Satire is also an act of transgression – it is not always nice, we do not always approve of it, but it does take us between the lines of our society, behind our taboos – which is a place where we sometimes need to go in order to challenge our assumptions.

Speaking as a journalist, there is yet another lesson I learned from my days in Berlin in November 1989. You cannot do real journalism or witness history from behind a computer screen or from reading books. If you want to see and tell the full story and find within it some kind of truth, you can only get it from real encounters in real places with real people.

However many sources you may draw from, however interactive you may be through your computer or through Facebook or Twitter or whatever other social media you may use, however many sounds or visual images you may be able to draw from, there will always be something missing. You need to be there. That is why I learned more from being in Berlin in 1989 than from anything I have read about the fall of communism since.

Of course, we cannot always witness history, we cannot be in several places at once. In such cases we need someone we respect and trust to be there for us, telling us the story as it is. That is why the journalists who go into harm’s way at times of conflict are true heroes. The broadcaster Edward R. Murrow accompanied Allied troops into Europe at the end of WWII. Thanks to his eye-witness reports for American radio we know what the conditions were like in the concentration camp of Buchenwald at the moment it was liberated in 1945. These accounts have helped to engrave the truth of what happened into our collective memory. The journalist is not just collating information. The journalist is evaluating and trying to communicate experience. This is a considerable burden of responsibility.

“My job is to bear witness”, is how the frontline American journalist Marie Colvin put it in one interview a few years ago. On February 22nd 2012, Marie Colvin was killed while doing her job – she was reporting on the shelling of Homs in Syria for Britain’s Sunday Times. At the time, a lot of people commented that she was being irresponsible and asking for trouble, going into a conflict zone when she knew the dangers.

I would argue the opposite: that people like Marie Colvin or the ten journalists who were murdered in Paris yesterday, remind us of what freedom – with all its untidy complexity – really is and how much it can cost.